Getting from the house to school in the morning – or rather the two schools that my youngest sons attend – always takes a while. Shmuel, like a seven-year-old version of the English poet, William Wordsworth, stops to marvel at the wonders of nature; while Pinhas, five, comports himself like a young Isaac Newton, pausing to consider how things work. Today, a garbage pick-up fired both of their imaginations. Shmuel seemed to be readying a sonnet; Pinhas an engineering diagram. Yes, getting to school takes a long time.

Between the flights of sublimity and the mechanical inquiries, I pursue another topic, “How to Cross the Street.” First, an undergraduate course in semiotics: “What do the thick white lines on the pavement mean?” “What does the blue and white illuminated image of the pedestrian represent?” “Yes, this is the place to cross the street!”

So we stand and dutifully wait. One car zooms by; and then another. A young father, with an mp3 player – probably listening to a lecture – his five-year-old daughter in tow, crosses down the block, away from the pedestrian crossing. I see Pinhas wondering: What exactly is abba trying to pass off on us? “You don’t have to cross here,” he finally affirms, another car whizzing by: “Look at them.” He points to his father and daughter still in sight and already at the grocery store across the street, poised to buy a white roll and chocolate milk.

I preempt the request I know is coming. “No, you can’t havelakhmania and choco, Mommy packed you a lunch.” And: “Just because other people do the wrong thing does not mean that it’s right.” Finally, a car stops, the driver waving us across benevolently. I nod in gratitude – in Israel, traffic regulations are often viewed as suggestions – “Thank you for abiding by the law.”

Pinhas is first to school today. Shmuel, sometimes shy, is reticent to accompany us, so he waits outside the school gates. A group of boys, pushing their heads through the metal bars, starts to tease him, even as I stand by: “You guys have a problem?” I ask, mimicking what boys typically say when taunting Shmuel, who has Down Syndrome. When I come back, Shmuel is still standing there. He looks confused, a departure from his wondrous happy, friendly self: one of the boys is standing with his tongue hanging out with a mocking stare.

When I return home, my wife asks: “What do you expect?” This was one of the schools that would not take Shmuel; why should we expect more from children than their teachers? Or, a principal who had told us – he has a niece with Down Syndrome, so he assured us, “I know” – that “mainstreaming is not good for special children.” Besides, he added, “it would give the school a bad name.”

We instinctively hate the other for reminding us of the “defect” which is our own.

The Torah enjoins, “Love your neighbor as yourself,” and in the same chapter of Leviticus, “You shall love the stranger.” Love the one with whom you identify, as well as the one who seems different from you. Rashi, the eleventh-century commentator who guides generations through difficult passages, writes that the Torah assumes one may come to hate the stranger because he has a “defect.” His deficiency, whatever it may be, arouses a desire to afflict him, or at least distance him.

But the verse continues: “You yourself were once strangers in the land of Egypt.” You see him as different, but he is just like you. The stranger’s so-called defect, Rashi writes, is your own. That characteristic which we are unable to acknowledge – too painful or unpleasant – we externalize in a hatred for others. We were once slaves in Egypt, “strangers in a strange land,” immersed in idolatry. So, we look at the stranger and project upon him that which we fear might be most true about ourselves. But we fear it – this is the Torah’s insight – because it is true. We instinctively hate the other for reminding us of the “defect” which is our own.

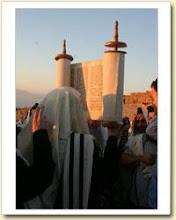

The answer to the question opening Hamlet – “Who’s there?” – is never simply answered. We have a natural propensity, the Torah tells us, to be in denial about our selves, but also to project onto others the perceived shortcomings from which we most want to escape. We hate the thing which – in a way we cannot yet face – helps to define who we are. Jewish prayer and ritual, as a corrective to those inclinations, refer to the God who took the Jewish people out of Egypt, not the God Who created the heavens and the earth, emphasizing: “Remember who you are, remember from where you came.” Your past – and you – are also exceptional. The verse concludes: “I am your God” – Rashi explains, both your God and the stranger’s. You are not only united in your history; you and the stranger, who you want to distance from the camp, have the same God. So be open-minded to the stranger within.

We may have more in common with children of difference, like Shmuel, than we are willing to admit.

In the end, we may have more in common with children of difference, like Shmuel, than we are willing to admit. The school principal’s protests about mainstreaming may reveal as much about his own personal insecurities – one is not always efficient, brilliant, and scholarly – as about purported concerns for the “name” of the school. The proximity of children with Down Syndrome, or exceptional children of any kind, make us uneasy about the ways in which we may also be merely ordinary, less than competent, imperfect. How else to explain a school – or a community – that wants to project an image of perfection in order to maintain its good name?

But that image is a communal fantasy, not the Torah’s ideal. Keeping special children out of the “mainstream” may be, in many cases, the right thing. But sometimes, it is as much about parents – or uncles – who nurture images of themselves helping them to forget what they do not want to know. As far as myself, I have a lot to learn from the indefatigably questioning and studious Pinhas, but probably even more from my more bashful Shmuel, who takes in the world in awe, and who laughs and dances with unselfconscious glee and abandonment. The stranger we try to flee almost always has an uncannily familiar face. But becoming more tolerant to that which is more singular in ourselves – acknowledging the stranger within – makes it easier to be tolerant of the exceptional in others.

Back on the morning trek to school, walking in the direction of Shmuel’s school now, we encounter the bouncy-gait of the nine-year-old Yehuda: “Good morning Shmuel!” Shortly after, a smiling boy on a bicycle, and an exuberant “Shalom Shmuel!” “He is my friend,” Shmuel boasts loudly. And then the gawky eleven-year-old from down the block, who keeps a rooster in our building courtyard, volunteers, “Can I walk with Shmuel to heder?” We are grateful to the school principal who declared, “It’s a big mitzvah” to accept Shmuel into the school. But the children in Shmuel’s school, like his brothers and sisters, perhaps benefit most in learning to take for granted – instead of taking exceptional at – including Shmuel in their play. For from a very early age, children notice the exceptions we make, and turn them into second nature, whether crossing the street in the wrong place or making a new friend, even though he may be a bit different.

No comments:

Post a Comment