by: Sara Yocheved Rigler

Nava’s doctor killed a woman. Not by malpractice. The woman was claiming that her baby was Dr. X’s child. He got fed up with her, went with a loaded gun to her apartment, and murdered her. Dr. X is now serving a life sentence in an Israeli jail for first degree murder.

Nava knew that people could make dramatic turn-arounds because in her own life she had transformed herself from non-religious Israeli to observant Jew. So she visited her former doctor in prison in order to encourage him to do teshuva[repent]. Dr. X was totally uninterested. All he wanted to talk about was how angry he was at his mother because she refused to visit him in prison.

Nava related this story at our family Shabbat table. It led to a lively discussion. I took the mother’s side. A human being is, I contended, the aggregate of his actions. A person who does good is good, while a person who commits evil deeds is evil. Why should his mother, who had given him a high level of education and every opportunity to become a mensch and an asset to society, visit a son who had willfully chosen to murder someone in cold blood?

Other guests at the Shabbos table disagreed. “What about unconditional love?”

I never got the concept of “unconditional love.” It’s not true that “you are what you eat.” Rather, “you are what you do.” How can you love your son the murderer? Your son the rapist? What exactly are you loving in the miscreant?

THE TOUCHSTONE

I have only one son, who was born when I was 46 years old after five years of intensive fertility treatments. Of course, I adore him and lavish on him love and attention. Many months after the discussion about the doctor convicted for murder, my son, then 14 years old, got into trouble in school. We got a phone call from the rabbi in charge recounting my son’s offense. With my volatile nature, I ordinarily would have let into my son, but my husband calmed me down and coached me on what to say when he came home from school.

“I thoroughly disapprove of what you did,” I told him, “but I still love you.”

My son’s impassioned response almost knocked me off my chair: “But you wouldn’t visit me in prison!”

"Your love has its limits. If I really misbehaved, if I did something terrible, you wouldn’t love me!"

Apparently he had taken in more of that long-ago conversation than I had realized. Now he was saying loud and clear: Your love has its limits. If I really misbehaved, if I did something terrible, you wouldn’t love me. Your conditional love for me isn’t good enough.

Since honesty had always characterized our relationship, I could offer no soothing platitudes. I shook my head and admitted, “No, if you murdered someone, I wouldn’t visit you in prison.”

This “wouldn’t visit you in prison” touchstone became a pebble in the shoe of our relationship. At regular intervals he threw it up to me. I realized that my profuse love for my son was like being allowed to live in a gorgeous home — complete with swimming pool and gym — but with the insecurity of knowing you could be evicted at any time. I would have to learn to love my child unconditionally, but how?

GOD’S LOVE

Rabbi Efim Svirsky once gave a class-cum-meditation in my home. He guided the assembled women to induce a meditative state, then asked us to experience “God is here now.” Check. I did it easily.

Next, he asked us to experience, “God loves you.” Check. I feel it all the time.

Lastly, he asked us to experience, “God loves you unconditionally.” Gulp. I ran into a stone wall.

My problem, I realized, is that I had no experience of unconditional love. My mother no doubt loved me unconditionally, but my father always loomed larger in my life. He was 44 years old when I, his only daughter, was born. He adored me and showered me with love. And I gave him good reason to. I brought home straight-A report cards, won a prestigious essay contest, got into the National Honor Society, was President of my synagogue youth group, was accepted at several top colleges, and graduated Phi Beta Kappa, magna cum laude. My father was always, as my mother put it, “bursting his buttons” with pride at my accomplishments.

But what if I had no accomplishments? Would he still love me as much? I never dared think about that frightening “what if.”

A person is, in essence, his core, his Divine soul.

When Rabbi Svirsky asked us to experience God’s unconditional love, however, I realized that I had to go deeper. Does God love me because of my accomplishments? No, God loves me because my soul is a spark of God’s own luminous Divinity. Just as a mother loves her newborn, sans accomplishments, because the baby is part of her, so God loves us because our soul essence is part of God. I was wrong in my contention that a person is the aggregate of his actions, like an onion that has no core. A person is, in essence, his core, his Divine soul. One’s actions are the layers of curtains that surround the soul, sometimes becoming so opaque and dark that they obscure the soul’s light entirely. But God made a covenant with our forefather Jacob that He would never allow a Jewish soul to fall below the point of irredeemability. That spiritual essence, what we call the pintele Yid, is always worthy of unconditional love.

After working to make this concept real in my mind and heart, one day I sat my son down and announced, “I would visit you in prison even if you committed murder. I’m there.”

He smiled broadly. Our relationship made a quantum leap up.

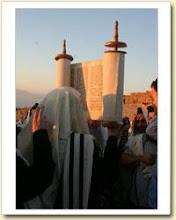

SUKKOT

By fulfilling the mitzvah of dwelling in a sukkah during the holiday of Sukkot, a Jew is literally surrounded by the Shechina, the feminine Presence of God. This is generally conceived as the “reward” for the repentance the person undertook during the Rosh Hashana-Yom Kippur period. Now that the soul is cleansed of its dross, the person can dwell in God’s presence in the sukkah.

But what if a person fails to repent? We are taught that for a person to attain atonement on Yom Kippur, the person must have passed through the stages of teshuvah: admitting, regretting, and resolving to change (plus, if he hurt another person, seeking that person’s forgiveness). What if a person didteshuvah on some misdeeds, but not others? Or didn’t do teshuvah at all? Then he enters the sukkah with his misdeeds still clinging to his soul, as if dressed in filthy, stinking rags. Is such a soul still visited by the Shechina when sitting in the sukkah?

The answer is “Yes!” There are no admission criteria to the sukkah. You don’t have to have an “I-did -teshuvah ticket” to get in. The feminine Divine Presence descends and hovers over and around the sukkah, whether it is inhabited by saints or sinners. And since this gross physical dimension is often in Jewish parables considered a prison for the soul, that means that during Sukkot God’s “Mother aspect” visits Her child the sinner in prison.

As you sit in the sukkah this week, think about that and feel God’s unconditional love.

No comments:

Post a Comment